After the Fall

Ten Days in Post-Assad Syria (part 1 - Damascus to Musa al-Habishi)

The journey around Syria was my first every guided trip (other than a safari which was quite different), so I have no other such trips to compare it with. I can only say that, for me, the organisation and guiding was exceptional. The trip was booked through Safar Expeditions (thanks Nicole) and expertly shepherded by Wasim Bahra whose knowledge and contacts were exceptional (this is not a paid advert).

Faces of some of the trip members are obscured at their request.

Syria. A country full of hope, full of happiness, full of fear and sadness. Hope for the future, fear that everything may re-descend into a quagmire of ethnic or religious violence and hope and happiness that the violence has, largely ended giving hope for a better future. And with all that, immense sadness for what has been lost and destroyed.

The entry and exit into Damascus, like in many countries of the global south is a mixture of chaos and celebration. The bus breaks down, leaving thirty of us standing on the aircraft steps in the hot sun. Underneath the baggage tractor appears to be broken as it belches fumes and noise while going nowhere.

Once inside, ten of us stand around like lost souls staring at the closed visa office until someone tells us that the new one is forty metres on and to the left. Nothing tells the clueless visitor this information. Meanwhile, all around, people are hugging and greeting relatives and friends they may not have seen for ten years or more. There is unbridled joy.

For us, over the course of our stay, that joy is translated into a never ending round of greetings and welcome. Everywhere we go people greet us, welcome us, want to help, invite us to their houses and want to take selfies with us. Any Syrian under about fifteen years of age has no memory of foreign tourists. For many Syrians our presence, gives a sense of both returning normality and hope that the economy will slowly start improving.

The taxi ride to old Damascus takes 30 minutes. Everywhere there is the residue of war. Destroyed buildings, rubble, bomb damaged buildings, half finished buildings, half occupied buildings. It seems every third building, still standing, is empty.

Up to a third of Syria’s population fled their homes during the war and most have not yet returned. When the war started, things just stopped. The skeletons of half finished projects stand waiting for developers, owners, finance or skilled labour. Slowly people are creeping back. The number of flights into Damascus increases monthly. But they are cautious. Will things stay calm? Will there be jobs?

Before visiting and after departure people constantly ask “Is Syria dangerous”? Of course it’s not entirely safe but, I say, safer than a myriad other countries and activities. Do you live in the U.S? 11,000 people die annually from gun deaths. Do you drive? Then you are in greater danger than when visiting Syria. When I lived in Turkey it was the same question. The same racist question. At that time, in 2017, you were far more likely to be killed in a terrorist incident in the UK or France.

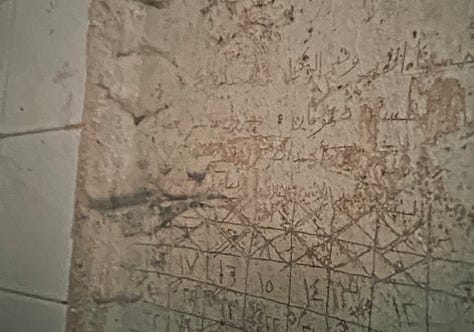

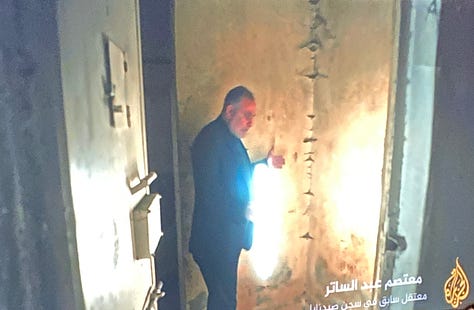

Our first day takes us to the Damascus Opera House to see an Al Jazeera documentary by film director, Abdo Madkhaneh, on the infamous Saydnaya Prison. With each passing week more mass graves are found and over 100 of Assad’s torture centres have been found within military bases and other ex-Government facilities. Some estimate that up to 1.5 million were killed or disappeared.

Former inmates, some detained for up to 17 years, talk about their ordeals. Even without the benefit of sub-titles the anguish and horror of the place seep through. They show us the execution room where up to six at a time were hanged. It is hard to understand the brutality of humans to each other.

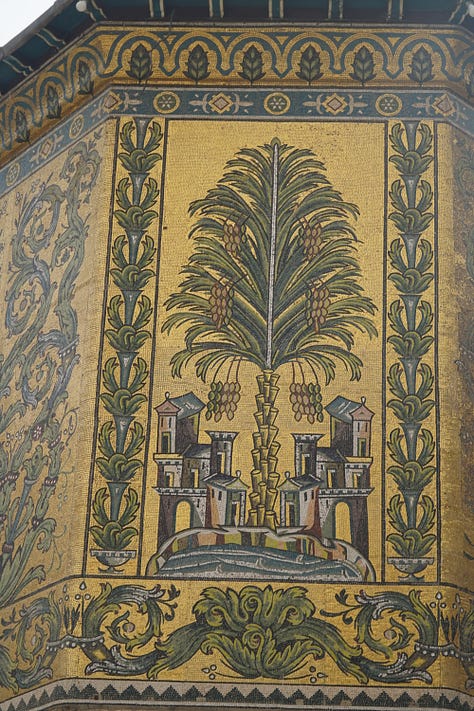

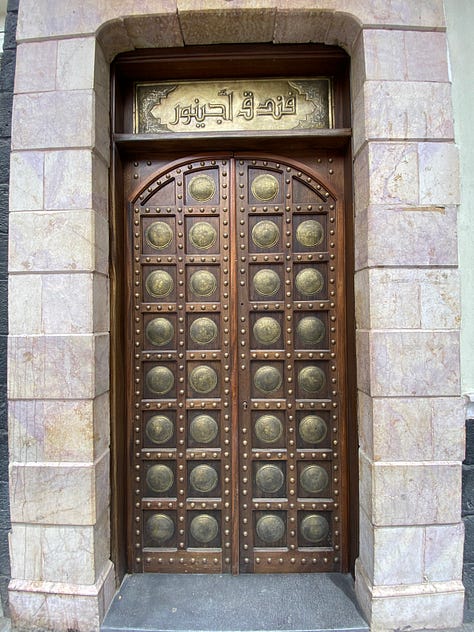

In Damascus we stroll the souk answering questions about our origins and our visit. Unlike Aleppo the old city of Damascus was not damaged in the war as it was the centre of Assad’s military and so the delights of the old city are intact.

One could spend a full day doing nothing but stroll the souk, drinking in its atmosphere, sampling, eating and talking but the rest of the old city calls including Umayaad Mosque and the Azam Palace. Many of the former houses of the wealthy have been converted to restaurants and hotels. The streets are full of people carrying on traditional crafts.

Along Straight Street, Damascus, we are traversing the main Roman road, of which the western half is today called "Midhat Pasha Street," while the eastern half, leading to the Bab Sharqi gate, is known as "Bab Sharqi Street" Here we are offered free bread and we buy some of the world’s largest croissants, while watching the intricate work of decorating copperwork with inlaid silver.

Straight Street is believed to be the site where Paul was baptized by Ananias, an event recorded in the Acts of the Apostles (assuming one believes anything written in the Bible) and the church of St Ananias is close by.

From Damascus we head out on the road north that will take us to Homs for the night and eventually lead to us to Aleppo.

En route we will stop at Maaloula and Deir Mar Musa al-Habashi. All of these are destinations worth visiting but the pick is the monastery at Musa al-Habishi. Here at this ancient and now restored monastery one can stay the night and view the outstanding ancient frescoes in the church which is shared for worship by Christians and Muslims alike.

Maaloula is a small Christian community in the hills which boasts two ancient monastic communities of the Convent of Saint Thecla and the Church Of Saints Sergius & Bacchus, the latter being one of the oldest churches in Syria. In addition it boasts the famous Blue Wine and one of the last Aramaic speaking community, Aramaic being the language spoken by Jesus.

From Musa al-Habishi we wend away through the semi-desert to Homs. 50 years of Assad regime corruption and the last ten years of war have drained Syria dry. Now it is dealing with the longest drought since 1980 and instead of wildflowers the only things ‘growing’ in the desert are the millions of plastic bags and other items that have caught on the desert plants. Syria doesn’t have the infrastructure to deal with its rubbish or much else that is urgently needed.

Next, part 2 : Homs, the abandoned cities and Aleppo.

See other posts on: Writing From the Road